REVITALIZING TRADITION: TONO MIRAI

ARCHITECTS' OYAKI FARM

This large-scale project takes advantage of local wood and soil to blend in with the surrounding mountain range. A bastion of architectural excellence, Oyaki Farm merges traditional Japanese construction techniques with contemporary methods.

THE PROJECT: OYAKI FARM BY TONO MIRAI ARCHITECTS

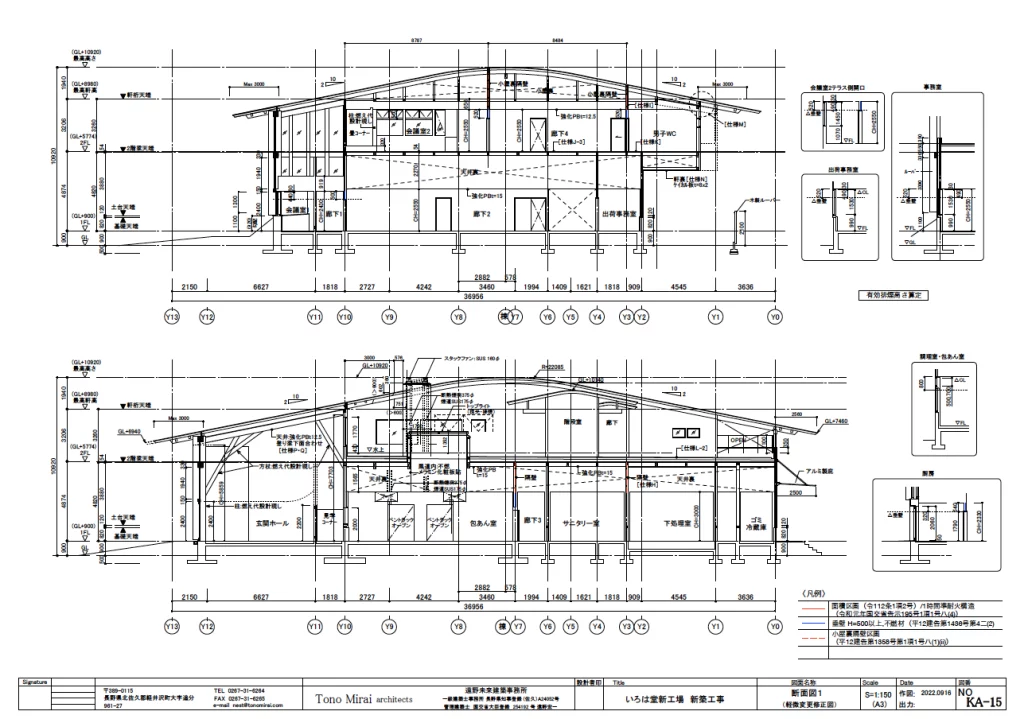

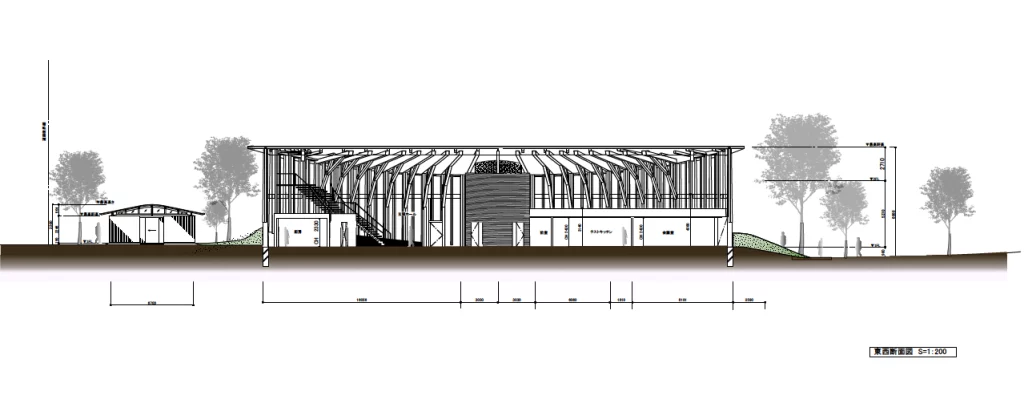

The roof is a large, softly curved structure created using advanced hand-chiseling techniques. The arc-shaped roof, designed to meet Japan’s primary energy consumption standards, harmonizes beautifully with the surrounding mountains.

A portrait of Tono Mirai, founder of Tono Mirai Architects.

This entire building, spanning an impressive 1,500m2, is crafted from semi-fire-resistant wood, primarily using cedar and cypress. On the north side, a glass curtain wall, adorned with cedar drum pillars stretching up to seven meters in length, allows natural light to flood the space.

Every intricate detail in the Oyaki project tells a tale of craftsmanship and tradition. Cedar beams and purlins rest upon sturdy cypress beams, forming a roof adorned with a 3-meter overhang of the eaves. This design not only showcases the timeless elegance of Japanese fan rafters, a technique passed down through generations, but also serves as a testament to the ingenuity of the human spirit. The toplights of the rammed earth wall, alongside the high side windows that invite natural ventilation, and even the gentle cascade of rainwater from the roof, all serve as conduits, juxtaposing sky and land. In doing so, they play an integral role in reducing the building’s CO2 emissions.

AN ODE TO MOTHER EARTH & JAPANESE TRADITION

The word “Oyaki” encapsulates the project’s deep respect for Japanese heritage. A baked food made of vegetables and wheat, Oyaki finds its roots in the Shinshu region of Japan. The name serves a dual purpose — as a fitting moniker for a café and a respectful nod to tradition.

It aspires to be a testament to the harmonious connection between human innovation and the earth itself by using locally sourced lumber and surplus soil from construction sites.

According to the architects, the use of these materials constitutes the structure’s harmony with nature — over the next thousands of years, the structure will “return to the earth” due to the natural, local materials present.

The symbolic glass-enclosed circular hall will have thick wooden pillars and a wooden curtain wall. The lumber used is almost 100% solid cedar and cypress from Neba-mura, Nagano Prefecture.

“Architecture is a physical entity, but ultimately it’s something that works on the human spirit,” said Tono Mirai, founder of Tono Mirai Architects. “I believe in three ecologies that all play large roles in the longevity of architecture — spirit, society, and the natural environment.”

SPIRITUAL ECOLOGY

The project site was once a “pit dwelling” settlement in the Yayoi period roughly 2,000 years ago, according to Mirai. Excavating the site revealed many red artifacts, the memory of which are reflected in the building’s 5.2m-high entrance hall and the foundation that rises along a natural slope. The restrooms, rest area, and main body of the building echo the building’s circular roof. Mirai said that these elements connect the site’s former settlement with its future.

SOCIETAL ECOLOGY

In consideration of societal ecology, the second aspect involves utilizing indigenous timber, local craftsmen, and traditional carpentry methods rooted in age-old knowledge to preserve both materials and skills while fostering community interconnectedness.

According to Mirai, one issue in modern Japanese wooden architecture lies in the abandonment of traditional carpentry methods in favor of hardware and pre-cutting machinery, neglecting the invaluable knowledge passed down through generations. The art of Japanese carpentry, encompassing wood framing, joinery, and finishing without reliance on hardware, is at risk of fading away without proper training and preservation, he explained.

In response, this project seeks to bridge the gap between ancient wisdom and contemporary design, reimagining the essence of Japanese architecture for the modern era.

ENVIRONMENTAL ECOLOGY

Regarding the environmental impact, the gracefully curved roof and gently sloping terrain create a seamless integration with the natural surroundings of the site, including the nearby mountains, trees, and lawn. The entrance hall, constructed from leftover earth materials, is illuminated by a skylight that symbolically bridges the gap between heaven and earth. The wooden curtain wall, maintaining the natural curvature of logs, connects the building to the conifer forest, preserving the region’s original landscape.

According to Mirai, one issue in modern Japanese wooden architecture lies in the abandonment of traditional carpentry methods in favor of hardware and pre-cutting machinery, neglecting the invaluable knowledge passed down through generations. The art of Japanese carpentry, encompassing wood framing, joinery, and finishing without reliance on hardware, is at risk of fading away without proper training and preservation, he explained.

In response, this project seeks to bridge the gap between ancient wisdom and contemporary design, reimagining the essence of Japanese architecture for the modern era.

Additionally, eco-friendly features such as modern water purification technology, well water usage, and heat recycling from the factory for café heating and cooling, showcase a commitment to sustainability. With ample natural light from high windows and energy-efficient LED lighting throughout, the building harmoniously blends with the mountainous backdrop. The arc-shaped design of the north entrance ensures a welcoming and unobtrusive entrance for visitors.

DESIGNING WITH VECTORWORKS

Mirai said that the most challenging aspect of this project was creating the different shapes and dimensions for the columns and connecting beams. Each rises at a different angle and is shaped differently than the last. Though the creation of models for these curved beams was outsourced to another architect using a separate software, the models were imported into Vectorworks for final detailing and to capture section and elevation views. These drawings were then given to contractors, who hand-carved the wood.

“For a designer like me who thinks of architecture not in terms of systems and numbers, but in terms of images and sketches then draws them and finally translates them into numbers, using Vectorworks to create organic architecture is a very enjoyable process,” Mirai said. “All the designers [at Tono Mirai Architects] are very happy to work with Vectorworks. Vectorworks is also very good at producing beautiful drawings with a high level of graphic expressiveness.”

All images in this article are courtesy of Tono Mirai Architects.